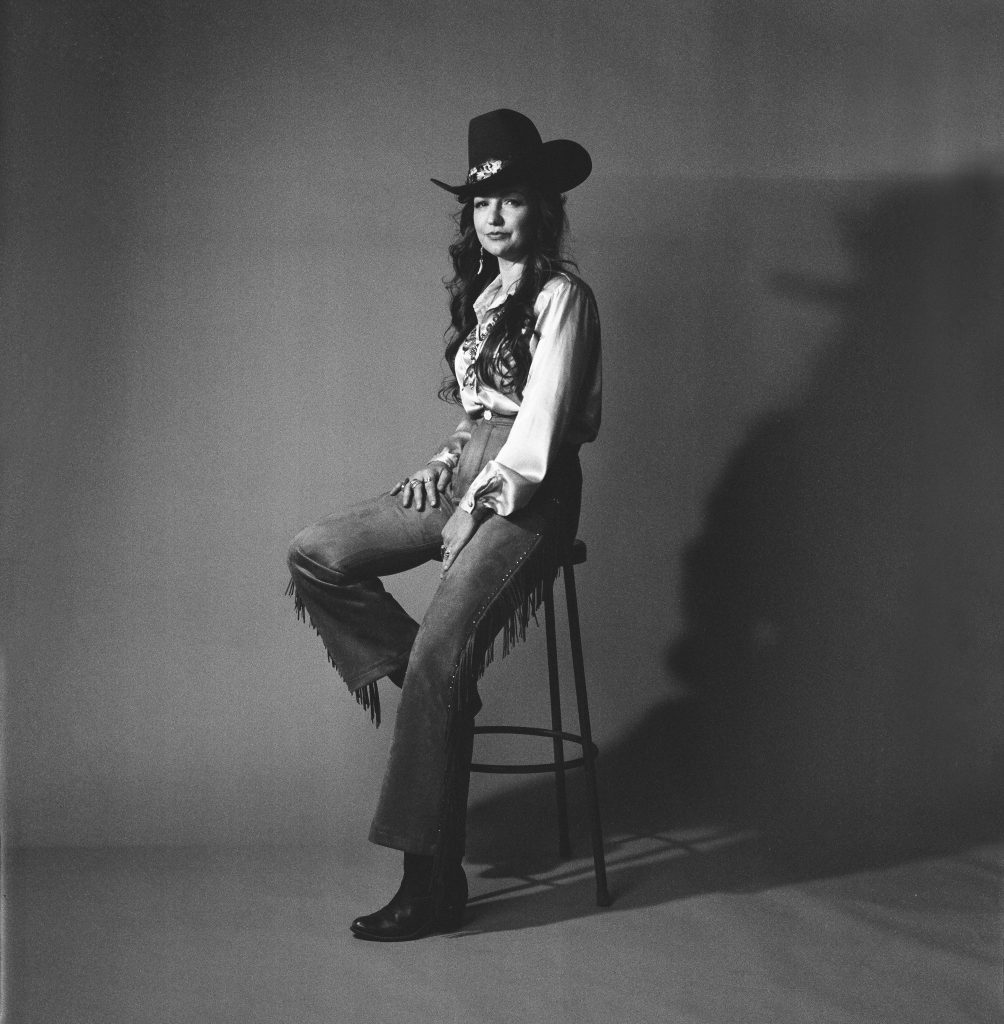

In the six years since she signed to John Prine’s Oh Boy Records, Kelsey Waldon has earned wide praise for her “self-penned compositions [with] the patina of authenticity” (Rolling Stone). On her new album, Every Ghost, she confronts addiction, grief, generational trauma, and even herself — and comes through it stronger and at peace.

“There’s a lot of hard-earned healing on this record,” Waldon says of the nine-song project, recorded at Southern Grooves studio in Memphis with her band, The Muleskinners. As she sings in the record’s title track and first song, “Ghost of Myself,” she’s put in the work not only to better herself and leave behind bad habits, but also to learn to love her past selves.

Doing so wasn’t easy, Waldon admits. “It took time and experience,” she says, adding that she can now find compassion for her younger self.

“I think you’ve gotta respect her,” Waldon says, “because she was trying as hard as she could for where she was at, and she was doing a damn good job.”

Compassion is a throughline on Every Ghost, whether it’s for Waldon herself, for the person in the throes of addiction in “Falling Down,” or for a suffering world in “Nursery Rhyme.” The people in Waldon’s songs aren’t irredeemable — they’re struggling.

“You’ve got to have compassion; you gotta stay humble and have gratitude,” Waldon says. However, she’s learned that you also can’t let people take advantage of an empathetic heart. “Comanche” — which Waldon jokes is her very own truck song — finds Waldon grappling with the loss of a loved one, not to death but to boundaries she’s set for her own good. Waldon owns a 1988 Jeep Comanche, and driving it serves as a kind of therapy for her.

“I love the whole aspect of when design mattered,” she says, “and owning your car was an expression of yourself.”

“Comanche” is deeply personal, but Waldon’s most introspective reflections bookend My Ghost. Its penultimate song, “My Kin,” extends the idea of loving yourself in spite of yourself beyond the choices she’s made and the circumstances she’s put herself in, to reckon with both the good and the bad that come from her family tree. Those traits, Waldon concludes, make her who she is.

“As the song says, ‘I’m the best and worst of my kin,’ and I love that for myself,” says Waldon, who was born and raised in a hunting lodge at the end of a dead-end road in the rural, unincorporated community of Monkey’s Eyebrow, Ky. “And I’m also at a point where I’m willing to break these cycles, I’m willing to grow, I’m willing to evolve.”

Among those best parts of her lineage is Waldon’s grandmother, who died in June 2024. “She was a remarkable woman. The women in my family have been rocks, and they’ve all been colorful and full of character,” Waldon says.

“Her garden and her yard, that might have been one of the things she took the most pride in,” Waldon adds, recalling how her granny would often stop to dig up roadside flowers, then transplant them into her yard. A display of tiger lilies, some of which now grow in Waldon’s yard in Tennessee, was a particular point of pride.

“Transplanting is such a tradition — it can teach you a lot,” Waldon says. “Life goes on, beauty can grow from anywhere, and as long as a person is remembered, they’re never gone.”

Waldon honors her granny with the song “Tiger Lilies.” She didn’t want an over-the-top sentimental song, so she instead leaned into the idea of traditions as a way to remember loved ones. “I’m sure Granny would love it,” Waldon says.

Every Ghost concludes with a Hazel Dickens cover, “Ramblin’ Woman.” Waldon covered two Dickens songs on 2024’s There’s Always a Song and had added “Ramblin’ Woman” to their live sets as well. While Waldon didn’t originally intend to include their cover on this album, it served as “a sonic star” during the recording process and has a message Waldon feels is still relevant decades after Dickens wrote it.

“Hazel was ahead of her time,” Waldon says. “Our existence is more than just what society expects of us. We’re more than just somebody’s girlfriend or wife or mother, and those are all beautiful things, but we can have our own independence, and we don’t have to do it for anybody else. We’re beautiful, magical, and powerful creatures.”

That’s certainly how Waldon sees herself after completing Every Ghost. “It feels like there’s a spirit of fearlessness throughout this album,” Waldon says, “and I’m really proud of that.”

Waldon’s fearlessness is among the reasons she landed at Oh Boy Records in 2019, as the independent label’s first new signee in 15 years. It’s attracted fans to her headline tours and her festival sets, and prompted artists including Tyler Childers, Charley Crockett, Robert Earl Keen, Margo Price, and Lucinda Williams to invite her on tour. It helped earn her both the title of “Kentucky Colonel” — an honor recognizing goodwill ambassadors of Kentucky’s culture and traditions — and a spot in the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum’s annual American Currents exhibit in 2024.

“True outlaw shit is sticking to your guns, and I feel like I’m doing that,” Waldon says. “I’m not saying I’m unbreakable, but I feel almost unbreakable. I’ve already hurt the worst that I could and lived to tell the story. We can be thankful for our ghosts.”

Connor Jay Liess

One local’s account: “That Connor Jay fella? Yeah, I’ve heard of ’em. Plays Americana/Idaho mountain music on this old beat up guitar he calls ‘Pickaxe’ while keeping time with the toe of his boot. Locals say he got his start playing for the crickets and crows up in the mountains above Boise. Weren’t long before his sound reached the ears of misplaced locals driving round on the backroads, who would stop and sit with him around the fire. Ol’ Willie Benson says he saw the man put down a liter of Old Crow before he even finished his set — that’s the rumor anyway.”

Whether the whiskey rumors are true or hogwash, one thing is for certain. Connor Jay cut his teeth playing guitar in the mountains in Southwest Idaho. When the noise complaints started coming from the apartment neighbors nextdoor, ol’ boy took to the hills and woods to find solace and a captivated audience of various critters. After time, he met the likes of one local songbird, an angel by the name of Christy Rezaii, who cracked his shell of comfort and showed the feller the world that was bluegrass and folk. It was this relationship and the all-inspiring locale of the Boise National Forest that set Connor Jay forth on his musical course.

“Americana grit, seasoned by campfire smoke,” is how he’s best tried to describe his style of music. It’s no one genre — because quite honestly he sucks at all of them. Rather it’s a hodgepodge of Idaho roots music that strives for nothing more than to just be unique and as enjoyable to spectate as it is to perform. You might hear a traditional bluegrass tune followed up by a slow country murder ballad or a folksy love song. You just don’t know. So sit back, uncork the corn liquor, and enjoy the show.

And drop a nickel in his gold pan. He likes that.