A Lone Star sheriff hunts quail on horseback and keeps a secret second family. A

mechanic lies among the spare parts on the floor of his garage and wonders if he can

afford to keep his girlfriend. A troubled man sees hallucinations of a black dog and a

wandering boy and hums “Weird Al” songs in his head. These are some of the strange

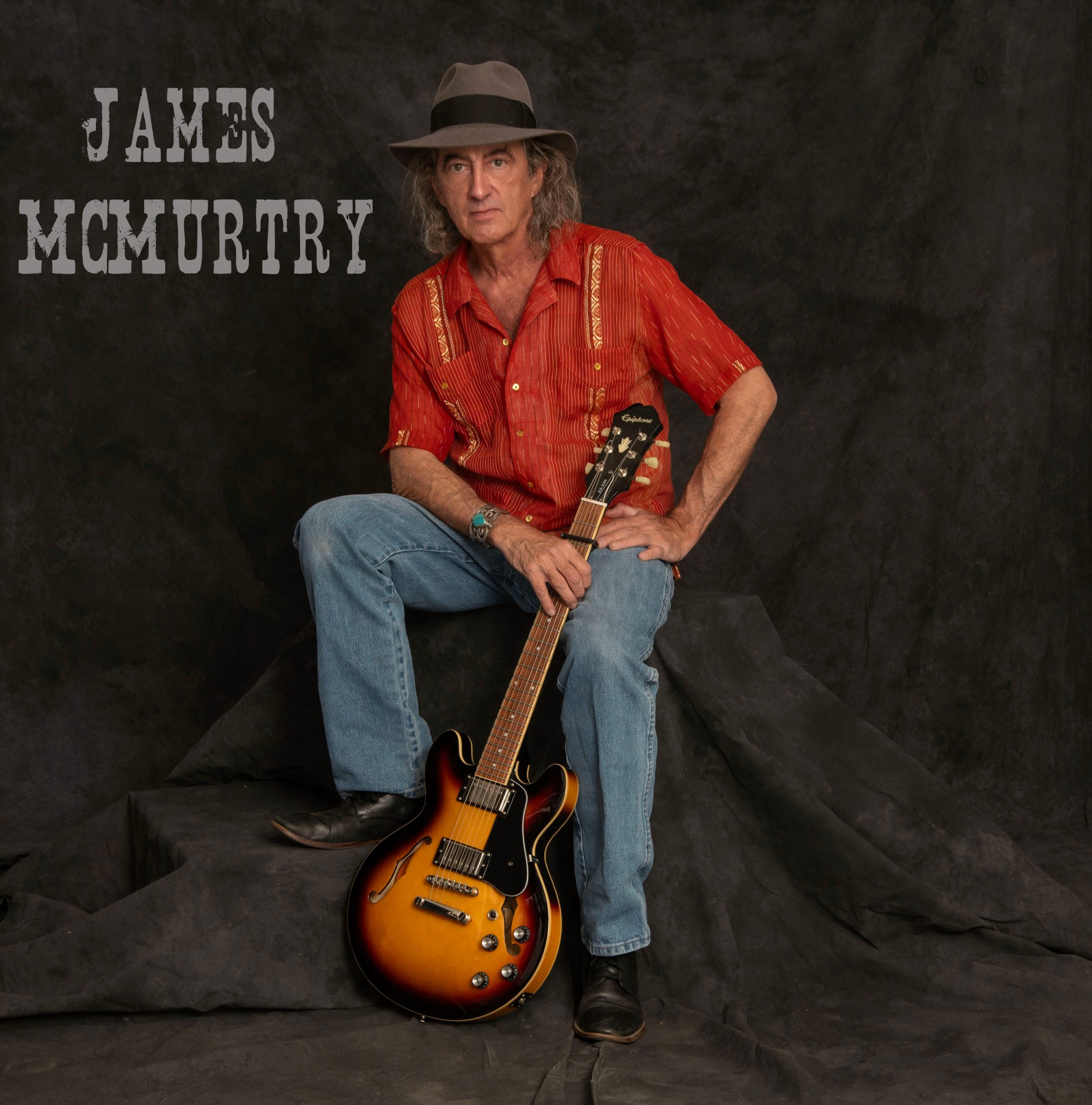

and richly drawn characters who inhabit James McMurtry’s eleventh album, The Black

Dog & the Wandering Boy. A supremely insightful and inventive storyteller, he teases

vivid worlds out of small details, setting them to arrangements that have the elements of

Americana—rolling guitars, barroom harmonies, traces of banjo and harmonica—but

sound too sly and smart for such a general category. Funny and sad often in the same

breath, the album adds a new chapter to a long career that has enjoyed a resurgence as

young songwriters like Sarah Jarosz and Jason Isbell cite him as a formative influence.

As varied as they are, these new story-songs find inspiration in scraps from his family’s

past: a stray sketch, an old poem by a family friend, the hallucinations experienced by

his father, the writer Larry McMurtry. “It’s something I do all the time,” he says, “but

usually I draw from my own scraps.” As any good writer will do, McMurtry collects little

ideas and hangs on to them for years, sometimes even decades. “South Texas Lawman”

grew out of a line from a poem by a friend of the McMurtry clan, T.D. Hobart. Driven by

gravelly guitars and a loose rhythm section, it’s a careful study of a man whose feelings

of obsolescence motivate him to take drastic action in the final verse. “Dwight’d stay at

our house way back in the ‘70s, when we lived in Virginia. During one visit he wrote this

poem about his father’s attitude toward South Texas. He wrote it down on cardboard,

and I came across it recently. There was a line about hunting quail on horseback, and

that was the seed of the song. I’ve lost the poem since then.”

The rumbling title track, a kind of squirrelly blues, features two mysterious figures who

appear only to those slipping from reality, yet it’s never grim nor especially despairing.

Instead, McMurtry namechecks a “Weird Al” deep cut and depicts a tortured soul who

doesn’t have to work a nine-to-five. He finds a defiant humor in the situation at odds

with the gravity of the source material. “The title of the album and that song comes from

my stepmother, Faye. After my dad passed, she asked me if he ever talked to me about

his hallucinations. He’d gone into dementia for a while before he died, but hadn’t

mentioned to me anything about seeing things. She told me his favorite hallucinations

were the black dog and the wandering boy. I took them and applied them to a fictional

character.”

Soon McMurtry had enough of these songs for a new record. “It happened like all my

records happened. It’d been too long since I’d had a record that the press could write

about and get people to come out to my shows. It was time.” What was different this

time was the presence of his old friend Don Dixon, who produced McMurtry’s third

album, Where You’d Hide the Body?, back in 1995. “A couple of years ago I quit

producing myself. I felt like I was repeating myself methodologically and stylistically. I

needed to go back to producer school, so I brought in CC Adcock for Complicated Game,

and then Ross Hogarth did The Horses & the Hounds. It seemed natural to revisit Mr.

Dixon’s homeroom. I wanted to learn some of what he’s learned over the last thirty

years.” During sessions at Wire Recording in Austin, McMurtry observed firsthand

Dixon’s grasp of digital recording technology as well as his instinctual approach to

tracking. “What Don’s really good at is being able to sense when it’s happening. He can

hear when it’s going down. If I’m producing myself and I don’t have him, I have to do

three takes and then go in and listen to them. Listening to those three takes can take

about 15 minutes. So Dixon’s ability to know when it’s happening is crucial, because it

can cut 15 minutes out of the day. That can really save a session, because you only have

so many hours in the day and only so much energy.

Working with McMurtry’s trusted backing band—Cornbread on bass, Tim Holt on

guitar, Daren Hess on drums, BettySoo on backing vocals—they worked to create

something that sounds spontaneous, as though he’s writing the songs as you hear them.

They were open to odd experiments, weird whims, and happy accidents, such as the

cover of Jon Dee Graham’s “Laredo” that opens the album. It’s an opioid blues:

testimony from a part-time junkie losing a weekend to dope. “We were playing a benefit

for Jon Dee at the Hole in the Wall there in Austin, and we thought it’d be good if we

played one of his songs. We rehearsed the song in the studio, and it sounded good. The

drums were ready. We’d already got the sounds up. Might as well record it.”

“Laredo” is one of a pair of covers that bookend The Black Dog & the Wandering Boy,

the other being Kris Kristofferson’s “Broken Freedom Song.” “I did that one a few weeks

after our initial sessions. It was just me and BettySoo, then we added drums and bass

later on. Kris had just passed not too long before we recorded it. I guess that’s why I was

thinking about him.” Like Hobart’s poem, it’s a bit of inspiration excavated from deep

within his own life. “Kris was one of my major influences as a child. He was the first

person that I recognized as a songwriter. I hadn’t really thought about where songs

came from, but I started listening to Kristofferson as a songwriter and thinking, How do

you do this? He was actually the second concert I saw. I was nine. He and the band were

having such a good time, and that really solidified for me that this was what I wanted to

do with my life.”

Once the album was mixed, mastered, and sequenced, McMurtry recalled a rough pencil

sketch he had found a few years earlier in his father’s effects. It seemed like it might

make a good cover. “I knew it was of me, but I didn’t realize who drew it. I asked my

mom and my stepdad, and finally I asked my stepmom, Faye, who said it looked like

Ken Kesey’s work back in the ‘60s. She was married to Ken for forty years.” The Merry

Prankster’s—Kesey’s roving band of hippie activists and creators—stopped by often to

visit Larry McMurtry and his family. “I don’t remember their first visit, the one

documented in Tom Wolfe’s Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. I was too young, but I do

remember a couple of Ken’s visits. I guess he drew it on one of those later stops. I

remembered it and thought it would be the perfect art, but I had to go back through the

storage locker. It’s a miracle that I found it again.”

It's a fitting image for an album that scavenges personal history for inspiration. Even the

songwriter himself doesn’t always know what will happen or where the songs will take

him. “You follow the words where they lead. If you can get a character, maybe you can

get a story. If you can set it to a verse-chorus structure, maybe you can get a song. A

song can come from anywhere, but the main inspiration is fear. Specifically, fear of

irrelevance. If you don’t have songs, you don’t have a record. If you don’t have a record,

you don’t have a tour. You gotta keep putting out work.”

PAST SHOWS

James McMurtry

BettySoo

James McMurtry

BettySoo

James McMurtry

Tylor Ketchum

SIMILAR ARTISTS