On Ricochet, her third album as Snail Mail, Lindsey Jordan returns to assert herself as a generational songwriter, clear-eyed and honest as ever. Time has passed, but she remains a sensitive soul, and here her incisive introspection is tethered to newly expansive and hypnotic melodies and ornate string arrangements. While writing Ricochet, Jordan found herself fixating on concerns she’d previously pushed out of her mind, namely death and what happens after. These 11 songs are colored by the anxiety of watching life slip through your fingers, as well as the vulnerability of loving deeply rather than frenetically. Ultimately, Ricochet is an album about realizing—and accepting—that the world still turns no matter what is going on in your tiny life.

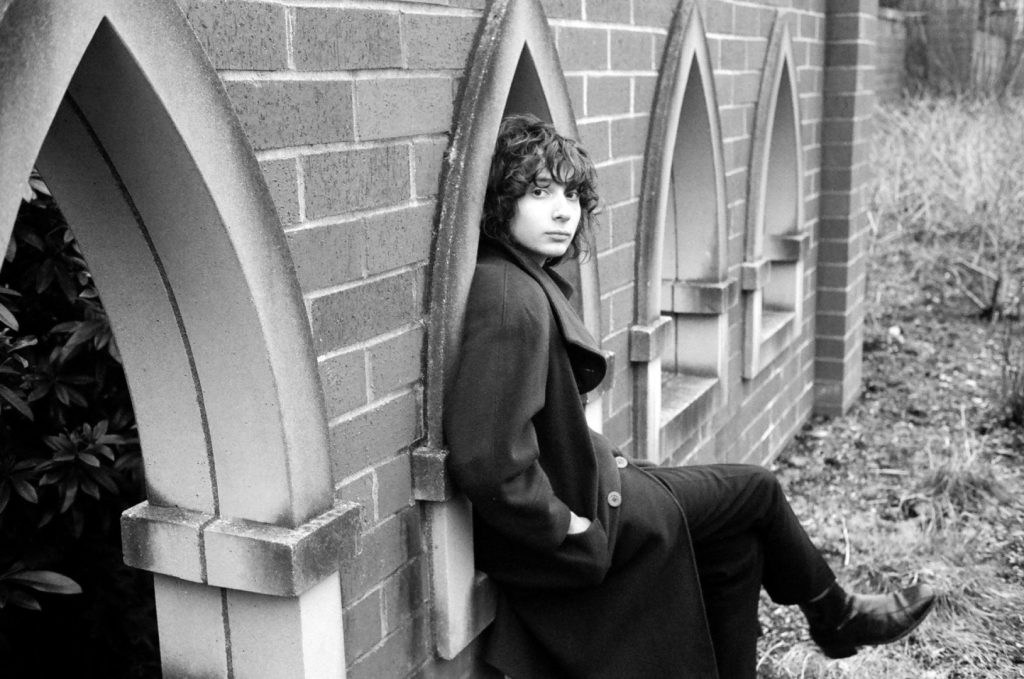

Ricochet is the first Snail Mail album in five years, and a lot has happened in the interim. Before touring 2021’s Valentine around the world, Jordan had surgery for vocal polyps. She underwent intensive speech therapy and emerged as a more confident vocalist—on Ricochet, Jordan wields newfound control over her voice, ironically enough for an album about uncertainty. She made her acting debut in Jane Schoenbrun’s indie horror I Saw the TV Glow, playing a Buffy-esque heroine with psychic powers. She moved out of New York, floated around for a bit, and landed in the area around Greensboro, North Carolina. She’s 26 and has a fluffy white puffball of a dog, whom she holds up to the night sky so she can see the stars.

All the while, Jordan was working on new music. She tried to write quickly—“which obviously didn’t work”—but with intention, aiming not to leave any material on the cutting room floor. “I’ve never done this before, but I wrote all of the instrumentals and vocal melodies on the piano or guitar, and then I filled in the lyrics all at once over a year,” Jordan says. “It takes me a lot more time and consideration to make great melodies than it does trying to connect things lyrically, so I gave myself more time to do the one.”

When it came time to record the songs bouncing around in her head, Jordan turned to a friend, Aron Kobayashi Ritch, the bassist and producer of the fuzzy indie rock band Momma. In winter 2025, they made Ricochet at North Carolina’s Fidelitorium Recordings, owned by R.E.M. producer Mitch Easter, and the Nightfly and Studio G in Brooklyn. Jordan describes the process as refreshing, trusting, and comfortable. “I felt like an equal voice,” she says. “He was as interested in my decisions as I was in his.”

Sonically, Ricochet sounds like the natural next step in Snail Mail’s small but mighty discography, building on the poised guitar parts of her 2018 Matador debut, Lush, and Valentine’s raw rock passion. Ricochet channels the Smashing Pumpkins at their sunniest and Radiohead at their most Britpop, with notes of Catherine Wheel shoegaze, Ivy power pop, and Sunny Day Real Estate emo. These are welcoming and vibrant tones of the ambitious ’90s alt-rock variety, embellished with unusual chords and curious textures that tickle the ear. (The most immediate and obvious descriptor is, ahem, lush.)

Jordan’s early music largely dealt with matters of the heart, a territory that she tried to step beyond on Ricochet. “Misery feels safe to write about because I am good at it,” she says, “but I’m not bathing in my own agony anymore.” To feel the pain of everything and then nothing is a lonesome contradiction. Ricochet is a record about being caught in this whirlpool, but Jordan’s music has never been so transcendent. The luminous opener, “Tractor Beam,” is driven by jangly guitars, but is ultimately about dissociation and “feeling othered while acknowledging that you’re spending a lot of your time and energy figuring out how to float away.”

While writing Ricochet, Jordan found herself drawn to art that explores the concept of life itself. The questions of artistic worth, ego, alienation, self-destruction, and failure posed by Charlie Kaufman’s 2008 film Synecdoche, New York cast a long-lasting existential shadow. “Nowhere” is informed by Laura Gilpin’s 1977 poem “The Two-Headed Calf,” about a young animal whose congenital condition allows it to see twice as many stars (the gentle stuff just kills her). On “My Maker,” she imagines flying a plane to heaven and overstaying her welcome at the airport bar. “Another year gone by,” she laments atop swirling guitars and spaced-out sprawl. “What if nothing matters?” “Oh, bouncer in the sky,” she wearily pleads on another song. “Let me in, I’m scared to die.”

Ricochet’s interiority reminds Jordan of Lush and other early music written in her Maryland childhood bedroom. “I was writing those songs for so long, my whole life,” she says. “It was my diary.” On the grunge-gaze song “Dead End,” she mourns the simplicity of a suburban adolescence, of parking in a cul-de-sac and smoking with friends.

“I’ve aged out of thinking that you’ll have everybody forever. Many of these songs are about friendships, friends that I’m sad about,” Jordan says, “But I’m also talking to myself.” “Looks like you made it/Somebody would be so proud,” she sneers on “Hell.” “But you isolated/Alienate your friends/‘Cus they’re just a means to an end.”

“Sometimes it’s devastating to be close with people. You’re busy during a birthday party. Then it happens again,” Jordan says. “All of a sudden, you haven’t talked to somebody you care about in years. You wake up one day and realize you’ve put yourself in a snowglobe, and it’s cold and weird and plasticy.”

To this end, emotional detachment can be self-imposed and involuntary, a protective impulse and a clinical blunting. “Numb myself out/What else should we do?,” Jordan sings on “Nowhere.” “You covered me all in kisses/I said I couldn’t feel it, but I wanted to.” Slipping into the abyss can become a comforting guilty pleasure. “Fireworks going off from above/Lit up the sky like lightning bugs/Felt so alive then, I can’t explain,” she sings on “Cruise.” “Couldn’t wait to get home and hide my face/Couldn’t wait to get home and slip away.”

Ricochet’s cover is the first not to feature Jordan’s face. Instead, a distressed deep blue expanse is filled by a spiral shell. A spiral moves in dual, opposing directions. Inward winding suggests contraction to the point of disappearance, while outward motion implies the promise of infinity. Distance and time may lead us away from the epicenter, and growth may be uneven, in fits and starts, and maybe a few steps backwards. It’s easy to get tangled up in emotions along the way, but every rotation offers the chance for pattern recognition, for perspective, for the realization that you do it to yourself, that’s what really hurts.

Sharp Pins

Fall in Love again with Sharp Pins’ Balloon Balloon Balloon

Sometimes it all goes POP!

Sharp Pins is the super solid lo-fi pop project of talented

Chicago musician Kai Slater of Lifeguard and Dwaal Troupe.

“Youth Revolution Now”

Armlock

Armlock make music for having your head in the clouds. On their new album, Seashell Angel Lucky Charm, the Australian duo of Simon Lam and Hamish Mitchell take you through a steady ascension into heavenly sonic realms. The band’s second proper release, and first for Run For Cover Records, Seashell Angel Lucky Charm taps onto the songwriters’ roots in experimental electronic roots and filters them through an indie rock lens, drawing the listener in close with crystal clear guitars, tight rhythms, warm harmonies, and sparse arrangements that leave room for character and eccentricities. The result is an album of inventively minimal music that does a lot with a little.

Friends for 14 years, Lam (vocals and guitar) and Mitchell (guitar and keyboards) have been in their fair share of musical projects together and apart. The two met studying jazz at Monash University in Melbourne, eventually discovering a shared love of electronic music. After a handful of electronic and dance outlets (I’lls, Couture, Kllo) Armlock came together through the band’s natural camaraderie and comfort with collaboration, and the two began incorporating guitar into the music they were making for the first time. Capable of recording and engineering the whole project themselves, the pair never needed to be precious with studio time. Instead they preferred venturing down songwriting rabbit holes, chasing down a feeling and layering ideas at their home studios, unsure where a song would ultimately land. “There’s no real distinction between writing, demoing, and final production, it’s all done at the same time,” says Lam. “It’s a workflow that is much more common in electronic music and how we started making music together.”

Seashell Angel Lucky Charm is the imaginative and sonically detailed result. The gentle vocals sit up front, often buoyed by fragile guitar lines and a simple but steady beat, and ample space is left for production flourishes like distant laughter, chopped up samples, and pitched squeals to ping around the listener’s ears. “We very much have a ‘throw stuff at the wall and see what sticks’ approach,” explains Lam. “We focus a lot on how an element sounds, rather than what an element is–if there’s a guitar part that’s not quite working, rather than try a different guitar effect or amp sound, we’re more likely to replace it with a keyboard, or a sample. A ‘sound’ is just as important as a ‘part’ to us, and I think that’s how a lot of electronic producers think.”

Every sound on Seashell Angel Lucky Charm feels precise and intentional, making the earcandy choruses on tracks like “Fear” and “El Oh Ve Ee” feel like expertly placed moments of guitar pop bliss. These two songs show Armlock’s savvy with harmony as they use octaves of angelic sounds to stretch a simple one-word chorus until it soars with meaning. Throughout Seashell Angel Lucky Charm, guitar is used sparingly and thoughtfully–more like a tool in Armlock’s belt rather than the primary songwriting vessel. On “Godsend” an airy acoustic provides the sturdy foundation, ushering the groove forward with uncomplicated chord progressions and leaving the focus on Lam’s voice.

Armlock’s sound at times recalls Pinback’s lean alternative, Alex G’s adventurous indie, or the wave of mysterious-yet-endearing genre-bending music coming out of the UK from label’s like Dean Blunt’s World Music or Vegyn’s PLZ Make It Ruins. Album opener “Ice Cold” provides a perfect entry point into Armlock’s world and their skill with coalescing disparate influences. One trap beat away from a Bladee track, the song begins with robotic voices reminiscent of Boards of Canada and evolves into the meditative warmth found in Adrianne Lenker’s more lo-fi work. There’s a subdued tenderness to Lam’s vocal delivery as he ponders the loss of a friendship and introduces the album’s fixation on air signs and higher dimensions.

Lyrically, Armlock’s music is often seeped with a very human desire to not only find guidance in the enormity of existence, but also to find something deeper in the mundane. “I was brought up Catholic, and I’ve definitely turned away from Christianity in my adult life but in recent years I’ve kind of missed that extra layer of meaning that religion adds to everyday life,” Lam says. “I’ve never written songs about that kind of thing, and it’s definitely pretty abstract, but it’s interesting to write about something that isn’t in my physical life but still feels like I’m talking about something ‘real.’”

Album highlight “Guardian” cuts to the heart of this theme with Lam looking “Somewhere up above” for “something or someone,” sifting through everyday life, trying to decide if the divine numbers he’s noticing on license plates are signs or happenstance. As guitar bends and piano rolls across the song’s structure until it fades into an airy soundscape where Lam yearns for a guardian through hushed vocals and chirping birds. “Ready for my essence to be found / ‘Cause I’m seeing their number all around / Guide me safe, lead me from harm / My seashell angel lucky charm.” Elsewhere these more esoteric ideas intersect with romantic longing, like on “El Oh Vee Ee” or “Godsend,” the former an upbeat earworm and the latter a richly produced cut of creative guitar pop.

Seashell Angel Lucky Charm manages to walk a fine line: impressionistic yet accessible, ambiguous yet refreshingly earnest. Armlock immerse you in their world but they don’t hold your hand, allowing you to be the one to discover the melodies and ideas within. It’s an impressive feat for only 18 minutes of music and it will leave you searching for more–and luckily you can hit repeat right away.