On Jellywish Florist invite listeners to question everything — to imagine a world where magic, surrealism, and the supernatural are our companions in day-to-day life. It dares to present a realm of possibility and imagination in a time that feels evermore prescriptive, limiting, and awful. The album finds Florist exploring life’s big questions without offering silver linings, morals, or definitive answers. Instead, the band asks perhaps the most difficult of questions: Is it possible to break free from our ingrained thought cycles and pedestrian way of life? That, Florist posits, may be the only way to be truly happy, fulfilled, and free.

Singer, guitarist, and principal songwriter Emily Sprague says that the record is purposely complicated. “It’s a gentle delivery of something that is really chaotic, confusing, and multifaceted,” she explains. “It has this technicolor that’s inspired by our world and also fantasy elements that we can use to escape our world.”

“We enter an observational fever dream about floating through liminal space between lifetimes, individual perceptions. There is reflection on our connectedness in joy and suffering through the wish for a peaceful place for our spirits to live and land,” Sprague explains. “‘Have Heaven’ establishes the world of the album to be not quite always lucid, but rather a perspective that is blended into the worlds of the magic and death realms swirling around us. The chorus is a chant that pleads for a better symbiosis between these worlds, and between our earthly forms trying to survive alongside each other, bound to the systems we must exist within.”

Jellywish is an exercise in multidimensional world building. The album’s panoramic cover art, which looks like something out of a Henry Darger volume, wraps the music in a collage of color that presents as science fiction-adjacent, hinting at something mysterious, fantastical, and mythological. Inside the album’s jacket, however, are tender and catchy sonic meditations on life’s most knotty subjects: life, death, earth, reality, relationships, joy, and pain. Taken together, Florist offers an acute sense of the band at this moment, one that worries about the world and its place in it. In contrast, it also presents an alternative to the doldrums of day-to-day life, and the necessary suggestion that very different things may be true at the same time.

With Jellywish, Florist offers a complex album in a time that is anything but simple. In mining the chaos and wonder of physical and spiritual worlds, the band holds a mirror to itself to the great benefit of all. It tells us that we are not alone, and challenges us to believe in magic.

Skullcrusher

And Your Song is Like a Circle, the second album from New York-based artist Skullcrusher, a.k.a. Helen Ballentine, winds its way into an everchanging, unstable core. Recorded piecemeal over a period of years following the release of her celebrated 2022 debut, Quiet the Room, And Your Song is Like a Circle does not capture experience – it gestures toward the imprint of an experience that is uncapturable. Swaying between vaporous folk and crystalline electronics, landing somewhere in the snowfields shared by Grouper and Julia Holter, Circle probes the ways that grief turns itself inside out. Loss itself becomes as real and substantial as what’s been lost.

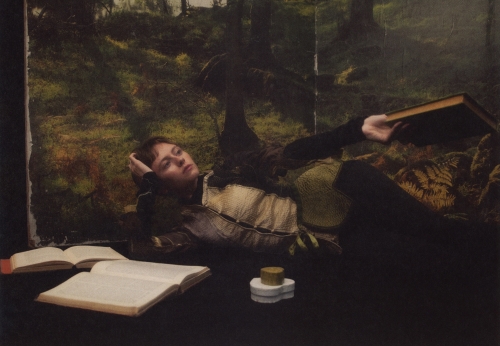

Ballentine began writing Circle after leaving Los Angeles, a city she’d called home for nearly a decade. She ended up returning upstate to New York’s Hudson Valley, where she was born and raised. Several years of intense isolation followed, and Ballentine immersed herself in films, books, and art that reflected the rupture of relocating cross-country and its dissociative aftershocks.

Throughout the record, the line between human and machine blurs. On “Maelstrom,” voices crash between echoing drumbeats like water through a cavern. The vocal filigrees on “Exhale” fan out into a haze of synthesizers and strings. “Dragon” lets piano echo over tight, gritted percussion.

If Skullcrusher’s first album rendered the detailed intimacies of domestic space, Circle finds itself vaporized across the landscape: swirling, drifting, searching. It skirts an event horizon in long, slow strokes. These are songs that vibrate with the fervency of an attempt to capture a moment, to draw a circle around it. “I like thinking about my work as a collection,” Ballentine says. “Eventually it might form a circle. Each time I make something, I’m putting another line around the body of work. It feels like I’ll be trying to trace it for my whole life.”